Hypermobility spectrum disorders (HSDs) refer to a group of conditions characterized by an increased range of motion in joints beyond the normal limits, often due to connective tissue laxity. More stringent criteria are applied in the diagnosis of hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hEDS).1 HSDs are increasingly well-recognized among young people and frequently attract referrals to healthcare providers across primary and secondary care.2 HSD and hEDS are often associated with chronic pain and other systemic features affecting physical and/or mental health. This article reviews these associations, considers approaches to assessing this cohort of patients and signposts useful tools that may improve outcomes.

The references used were identified using databases such as PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar and grey literature, including preprints and clinical guidelines.

Studies using the terms HSD, hEDS, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, management and chronic pain from 2005 to 2024 were included. Both primary research and reviews were considered. Resources were used if they investigated the association between hypermobility and pain, addressed clinical approaches to pain management and were peer-reviewed, presented original data or were a systematic review of the literature.

Studies focusing on unrelated forms of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome or purely genetic/biological studies without a clinical or pain management focus were excluded.

Each study was critically appraised based on its relevance, methodology and contribution to clinical practice. Emphasis was placed on the clinical relevance of diagnosing and treating HSD/hEDS and related pain. Sample size and population characteristics were considered to assess the generalizability of the findings, along with outcome measures, especially those related to pain, fatigue and quality of life.

This article does not encompass all existing literature due to article size limitations and its specific focus on clinical practice applications. Certain biological and genetic research on HSD was not included if it lacked direct clinical implications. Certainly, a thorough systematic review, including the comparative and contrasting views around HSD and hEDS, in addition to the above, could be an area for further exploration.

This methodology ensures a comprehensive and clinically relevant review of recent developments in the field of HSDs and pain management. The narrative nature of this article may introduce bias through subjective interpretation of study findings, although efforts were made to present a balanced view.

As this article used publicly available literature, no ethical approval was required.

Assessment of hypermobility spectrum disorders

Up to 20% of UK residents exhibit generalized joint hypermobility.3 HSDs, and especially hEDS, are recognized as being associated with both interoceptive and proprioceptive differences, as well as being linked to heightened anxiety and emotional dysregulation.4,5

There are various mechanisms linking HSDs to musculoskeletal pain. Hypermobile joints demonstrate laxity of soft tissues, creating instability, which can lead to microtrauma (resulting in tendonitis, bursitis, etc.) or macrotrauma such as subluxation/dislocation.6 There are also associations with pain in multiple other sites, including the head, gut and genitourinary tract.7 These are linked to entities individually diagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome, dysfunction of the gastrointestinal tract producing bloating and reflux or urogenital pain from dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia.7 Holistically, these diagnoses, while sometimes made in isolation, are often related to hypersensitivity of the autonomic nervous system. This dysautonomia can also be associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and migraine.8 Hence, pain may not necessarily be the patient’s main concern, and both fatigue and mental health issues are also strongly associated with hypermobility.9,10

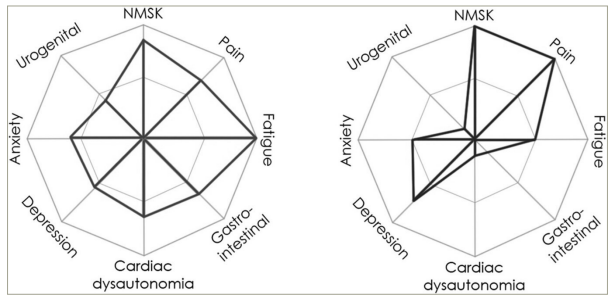

Well-recognized criteria, such as Beighton’s for joint hypermobility or the 2017 diagnostic criteria for hEDS, have limited value in diagnosing and quantifying hypermobility.11,12 However, Ewer et al. recently described ‘The Spider’, a screening tool with acceptable construct validity comprising 31 questions relating to eight domains that assess multisystem comorbid symptoms associated with HSD.13 Scoring generally uses a 6-point Likert scale (0–100), and the average of the domains provides an overall percentage. A higher score indicates a greater impact on daily living. The domains of pain, fatigue, depression, cardiac dysautonomia and gastrointestinal and neuromusculoskeletal (NMSK) symptoms all demonstrated strong correlations (r=0.7–0.8) with the respective comparator. The urogenital and anxiety domains showed moderate correlations (r=0.6). By using this, the clinician can focus on the symptoms that are the individual’s chief concerns and identify what specific support is needed most. This is a marked improvement on the system-selective approach often previously adopted, providing a visual representation of which symptoms affect the patient and to what degree. This can be seen in the examples shown in Figure 1.13

Figure 1: Examples of completed Spider graphs13

Reproduced with permission from Ewer et al. (2024) under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 attribution-noncommercial-noderivatives 4.0 international deed.13

NMSK = neuromusculoskeletal.

It is worth noting that these patient groups experience both physical and emotional pain, which are often difficult to distinguish but are represented on almost opposite sides of the graph. Patients are frequently referred to secondary care after escalating the analgesic ladder with no useful benefit. Indeed, patients with hypermobility are more prone to pharmacological side effects and accumulations of medication due to lack of efficacy or poor absorption, so clinician awareness of alternative approaches is essential.14,15 The definition of pain incorporates a variety of concepts, challenges and compromises. The definition was revised in 2020 to ‘An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage’.16 Importantly, the new definition is informed by the lived experiences of those suffering from chronic pain, and this approach has been warmly welcomed by the International Association for the Study of Pain global alliance.17,18 As a result, the recognition of multisystem involvement in pain has gained credence, and the association of different pain sites with HSDs has become more widely recognized and accepted.

Aetiology and associations of hypermobility spectrum disorders

Is there an inflammatory element to HSDs? Criteria for the diagnosis of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) were first proposed in 2010.19 MCAS is a dysregulation of the usually tightly controlled release of pro-inflammatory compounds. One theory is that the release of tryptase and histamine from mast cells can cause the proliferation of fibroblast and the production of poor-quality collagen, contributing towards hypermobility syndromes.20 Certainly, a significant overlap in the symptoms of MCAS with hypermobility and POTS has been reported.20,21

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a marker of inflammation, and its levels have been shown to be higher in those with chronic pain, even after adjusting for several biopsychosocial variations.22 However, measurements of other biochemical markers in MCAS (tryptase, histamine, etc.) often provide normal results unless assessed during symptom flares, which has fuelled the disagreement between clinicians over the value and validity of this diagnosis. Some clinicians are reluctant to recognize MCAS as a distinct disorder. It has been argued that some criteria are not sufficiently specific for diagnosis, while others are too stringent, excluding those with normal serum tryptase.23,24 Such controversies have recently been reviewed and addressed.25,26

Proprioception is often altered among those with hypermobility, especially among those with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.27,28 An increased range of joint movement is strongly associated with impaired coordination and balance. This developmental dyspraxia may be mitigated by exercises specifically aimed at strengthening muscles and improving balance. A recent study suggests that the active regulation of bodily position and action contributes towards emotional perception and expression, mediated by proprioception and interoception.29

Association of hypermobility spectrum disorders with neurodivergence

An important and recently recognized association is that hypermobility is over-represented among those with neurodevelopmental conditions.4 There is an increasing recognition and prevalence of neurodivergent conditions, particularly in young females. Until recently, neurodivergent traits were often disguised to minimize the risk of standing out and resulting in social exclusion. Such masking is now actively discouraged due to evidence of resulting adverse outcomes in later life.30,31 Multiple health conditions occur more frequently in this population, with hypermobility syndromes being particularly prominent.32 Adults with a neurodivergent condition are more likely to exhibit hypermobility than neurotypical adults, with an odds ratio of 4.51.33 In this study, neurodivergent people had both more orthostatic intolerance and musculoskeletal pain than the comparison group. Hypermobility mediated the relationship between neurodivergence and symptoms of both dysautonomia and pain.

Young people with MCAS have a 10-fold increased prevalence of autism.34 An association has also been described between neurodivergence and a heightened experience of pain.35 This may contribute to a disproportionate presentation of medical services by neurodivergent people, often with little to find on multiple investigations, leading to dissatisfaction and frustration for all involved. A recent study of nearly 500 self-selected individuals showed a strong positive correlation between musculoskeletal pain and autistic traits, in part mediated by hypermobility.36n However, the correlation with neurodivergent features was accounted for by fatigue, brain fog and dysautonomia (r=0.45), rather than by multiple pain sites (r=0.01). This suggests that dysautonomia plays a key role in the pain and non-pain symptoms linked to hypermobility, especially in neurodivergent people.

Association of hypermobility spectrum disorders with sleep disorders

There are several respiratory associations with HSDs, paramount of which is obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). This insidious entity can present with fatigue, disrupted sleep and headaches that are often overlooked. The classical description of OSA of a male with a high body mass index and marked snoring/apnoea does not represent the cohort with hypermobility.37 Laxity of cartilaginous tissue in HSD/hEDS can increase pharyngeal collapsibility, causing subtle symptoms in the absence of typical risk factors.38 It is also noteworthy that women (who are more likely to have HSD and hEDS) often present differently, with descriptions of insomnia, and are less likely to report apnoea or snoring.39 Therefore, it is worth actively asking about sleep hygiene and associated symptoms. If OSA is diagnosed and treated, a significant reduction in fatigue, dysautonomia and headaches is reported, along with improved sleep quality, mood and neurocognitive function.40 As this issue is commonly shared by patients who suffer from both HSDs and MCAS, the role of the gut microbiome may be relevant. Many foods can trigger MCAS in susceptible people, so it is important to strike a balance between avoiding these and maintaining a healthy intake of plant-based, high-fibre foods, which have been associated with reductions in pain and sleep disturbances.25 Highlighting these associations may encourage physicians to incorporate HSD into their differential diagnoses.

Therapeutic approaches to hypermobility spectrum disorders

The Spider Questionnaire can be used as a base for discussing a holistic approach to patients with HSDs. NMSK symptoms, such as joint instability, weakness, altered sensation, spasms and reduced proprioception, can lead to repeated injuries, falls and even reduced mobility. It is often poorly understood by the patient as well as medical professionals, leading to delays in treatment.41 Exercise focused on core and periarticular muscle strength can improve pain and reduce injury.42 There is also some evidence to suggest that closed kinetic chain and proprioceptive exercises can improve the above symptoms. Bracing, compressive clothing and taping also offer some benefit in joint protection and enhance proprioception.7 This is why a multidisciplinary approach, including our physiotherapy and occupational therapy teams who can educate and facilitate this, is central to managing the condition.43–45

Chronic pain is incredibly difficult to manage, and analgesia is always insufficient, leading to frustration in our patients as well as the prescribers.14 Supported self-management is a novel term for the combined concepts of educating and empowering patients to assess their pain and make active decisions on how to manage it with appropriate tools. This includes, but is not limited to, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), breathing exercises, group support, physical activity and the use/request of medication when appropriate.46 While these methods may initially be lengthy, in the long run, patient ownership of their health can reduce admissions/appointments. Emotional awareness and expression therapy (EAET), which targets trauma and emotional processing, is proving to be superior to CBT in complex older patients with chronic pain, and there is scope for incorporating this into clinical pain medicine, although further research and trials are needed to prove its efficacy.47

Fatigue is also challenging to address, with no single solution; however, a combination of good lifestyle practices may improve this symptom, which can be dominating. Good hydration, a balanced diet, ensuring adequate intake of essential vitamins (B12 and D in particular), minimizing caffeine and sugar intake, a gentle/gradual increase in exercise and good sleep hygiene can make a world of difference.15,48

A major feature of dysautonomia is POTS, and a simple but effective intervention is good hydration with required electrolytes and sugars. There is evidence to support exercise to reduce symptoms; however, it is worth explaining that this is a slow process over months, but it is becoming a standard part of the recommended management.7,49 Again, we accept that there is a wide range of opinions around the diagnosis and management of POTS, with some clinicians preferring not to recognize this condition and quite reasonably questioning the validity of self-diagnosis without consistent objective criteria.50

While we await more data on EAET, CBT – particularly ACT, which is one of the newer forms – is found to be beneficial in chronic pain, as it helps with improving pain interference, disability and low mood. Overall, it is found to improve quality of life. In the future, the focus may change towards individualizing treatments that are more suited to the needs of patients.51

Mindfulness has become increasingly popular in the treatment of a range of conditions and has recently been proposed to remodel brain function through neuroplasticity in patients with chronic pain.52 Pacing and modified exercise have been shown to be a core element of treatment in chronic pain associated with both fibromyalgia and hypermobility. A recent bibliometric study on this topic summarizes the recent evidence behind the approach.53

Based on the mast cell activation association previously discussed, a therapeutic approach involving combined histamine receptor 1 (H1) and H2 blockade is often recognized as an effective starting strategy for gastrointestinal symptoms, such as reflux, nausea and abdominal pain.20,54 Through the same mechanism, it may help with other systemic symptoms, with the subsequent addition of mast cell-stabilizing therapy such as montelukast or nedocromil.55

Future direction of research and therapy

Our research and understanding of HSDs and hEDS are still in their infancy, considering their prevalence and burden on the healthcare system. Some interesting areas for research include managing sleep disturbances in HSD/hEDS, genetic and biochemical markers associated with hEDS, exercise programmes/structures that work best and the wider implications of hypermobility for mental and physical health. Evidence suggests increased hospital admissions, but greater knowledge is needed about the reasons and how to support them in the community. HSDs have a complex array of symptoms, presentations and associations. This intricacy often leads to failed recognition, delays in diagnosis and challenging encounters with clinicians. Publicizing and acknowledging some of these associations should facilitate earlier diagnosis and a greater appreciation of the numerous facets of this condition, as it affects individual patients. This article highlights several areas for improvement in outcomes among patients with hypermobility, which can be absorbed into clinical practice.

Summary

-

Hypermobility is strongly associated with pain, which can be expressed in various ways and may fail to respond to traditional pharmacological interventions.

-

Hypermobility is associated with dysautonomia, which may manifest as mental and/or physical distress. The Spider assessment tool offers a valuable clinical adjunct.

-

Hypermobility is often seen in patients with MCAS and/or POTS, although the diagnosis and management of these conditions remain areas of intense debate.

-

Hypermobility is more commonly seen in a neurodivergent population, where its association with fatigue/brain fog may be partly explained by disordered sleep.

-

Hypermobility may be best managed through referral to a multidisciplinary team that can promote sustainable self-management programmes, supported by second- and third-generation CBTs, such as ACT and EAET, which offer promising results in pain control.