The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in treating cancer has greatly improved survival outcomes, particularly in patients with advanced disease for whom successful treatment options have previously been limited. For example, in patients with metastatic melanoma, the median survival time has improved from just 6 months to approximately 6 years with the use of ICIs.1 There are several different mechanisms of action used by the different ICIs, including anti-programmed cell death 1 (anti-PD-1, e.g. nivolumab, pembrolizumab and cemiplimab), anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 antibodies (anti-PD-L1, e.g. atezolizumab, durvalumab and avelumab) and anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (anti-CTLA-4, e.g. ipilimumab). While the benefits of ICI use are substantial, there is also a risk of overactivation of the immune system and subsequent development of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Common examples of irAEs include skin rash, colitis, pneumonitis, hepatitis and thyroid dysfunction.2 The mechanism by which ICI use results in various clinical complications is not completely understood but is thought to involve the activation of autoreactive T-cells, resulting in the disruption of immunologic homeostasis.3 Treatment recommendations for ICI-induced arthritis (ICI-IA) often include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, methotrexate, tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNFi) or interleukin-6 receptor inhibitors (IL-6Ri), but prospective evidence regarding therapy is lacking.4 Early evaluation by a rheumatologist is necessary, as the progression of inflammatory joint disease often leads to ICI discontinuation and could negatively affect tumour outcomes.

Epidemiology

The incidence of arthralgia and arthritis as irAEs varies between 1–43% and 1–7%, respectively.5 These incidences can vary as the location and degree of pain can be dependent on other factors such as the type of cancer or the concomitant use of chemotherapy or radiation.5 It has been shown that 78% of cases of ICI-IA are associated with PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 monotherapy, whereas only 10% of those who developed ICI-IA received more than one agent.6 There have been investigations into biomarkers that may predict who might develop irAEs.7–9 These have included auto-antibodies, blood counts and ratios, proteins, cytokines, microbiomes, micro-RNAs, human leukocyte antigen types and genetic variability. Unfortunately, most of the biomarkers studied provided indeterminate results, although there was a suggestion that the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may be useful as a predictor.8

Evaluation

Evaluation for ICI-IA should be performed if new or worsening joint pain or swelling occurs during ICI use or within 12 months of completing ICI therapy. A complete rheumatologic history should be obtained by a rheumatologist if ICI-IA is suspected. Physical examination should evaluate tender and swollen joints as well as evidence of tenosynovitis or enthesitis. It is important to distinguish if the history and physical examination point towards inflammatory or non-inflammatory arthritis, as non-inflammatory arthritis may be indicative of a newly described clinical entity of activated osteoarthritis associated with ICI therapy or of other common mechanical causes of joint pain, such as a rotator cuff injury.10 Laboratory studies are less helpful in determining the presence of ICI-IA compared with traditional rheumatologic disease. If laboratory investigation is pursued, one might include rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP), antinuclear antibody (ANA), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and creatine kinase (CK). RF and anti-CCP are only positive in 1.8 and 5.5% of individuals with ICI-IA, respectively.11 It is also important to note that ANAs can be positive in the setting of malignancy without the presence of an underlying rheumatologic entity. CK can be helpful in the setting of musculoskeletal symptoms to identify ICI-induced myositis. When obtained in the setting of ICI-IA, synovial fluid is notable for a CD8 T-cell response that differs from spontaneous autoimmune disease, suggesting that the mechanism by which patients develop ICI-IA may differ from psoriatic arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis.12

Imaging

X-rays should be obtained for the initial evaluation of ICI-IA to rule out other aetiologies of joint pain, such as metastasis, avascular necrosis or chondrocalcinosis. Plain films are often the most accessible and cost-effective imaging available but typically lack the sensitivity necessary to diagnose early ICI-IA.13 Ultrasound with Doppler and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be subsequently considered additional imaging modalities to evaluate for evidence of pathologies within the joint space. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) is often available from oncologic monitoring and can be used to identify areas of inflammation. Imaging can aid in the early recognition of ICI-IA to prevent the development of long-term or permanent joint pathology, as inflammation can persist for more than 6 months after discontinuation of an ICI.11 The reliability of ultrasound as an imaging modality has been demonstrated by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)-Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) system and can be used in the evaluation of synovial pathology, tendon pathology and the presence of bone erosions.14,15 Additional investigation for crystalline arthritis, particularly with the aid of ultrasound imaging, can also be performed to help distinguish amongst different entities associated with joint pain, such as gout and calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease.16 The most sensitive and specific modalities of imaging in the setting of ICI-IA are MRI and PET-CT, which are currently preferred.17 Both MRI and PET-CT can evaluate early evidence of inflammatory arthritis such as synovitis or synovial thickening, as well as features of more high-risk diseases such as bone erosions or oedema that result in permanent joint pathology.18 MRI can also be used in the evaluation of muscular involvement to assess for entities such as ICI-induced myositis or polymyalgia rheumatica as well as the response of inflammation to treatment.18 Unfortunately, the availability of MRI can be limited, and the cost of this type of imaging is more expensive than plain films or ultrasound. PET-CT does not consistently capture every joint that could be involved in ICI-IA, such as the hands or feet. Recommendations regarding initial imaging choice have not been studied, but beginning an assessment for ICI-IA with ultrasound and then pursuing MRI if imaging is equivocal would be a reasonable approach, as well as reviewing any PET-CT imaging available.18

Assessment and treatment

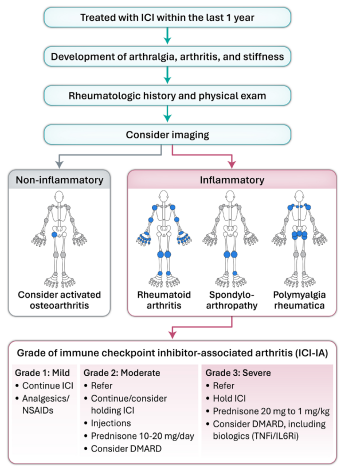

There are several different grading systems used in grading irAEs. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading can be used for arthralgia and arthritis, with grade 1 being mild disease, grade 2 being moderate disease impairing instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs) and grade 3 being severe disease impairing ADLs.19 The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) have created more specific criteria for grading irAE severity as well as guidelines for their management.5,20–22 A comparison of these different guidelines is available in Table 1, and an approach to evaluation and management is available in Figure 1. The EULAR selected a committee that was tasked with creating a consensus on the diagnosis and management of irAEs.23 They concluded that in contrast to other types of irAEs, rheumatic irAEs often tend to persist longer and that ICI-IA specifically tended to be persistent in the majority (53.3%) of patients at their follow-up visits following ICI discontinuation.11,23 They also noted that remission is not necessarily the target as in traditional rheumatologic disease because maintaining effective cancer immunotherapy may take priority. Prompt referral by oncology and facilitated access by rheumatologists are encouraged to enable an interdisciplinary approach to these patients’ care. In addition, they highlight that the field is continually evolving, necessitating the education of rheumatologists and that the rheumatologist’s role is to assist oncology in establishing a diagnosis and management.23 These resources are valuable in the evaluation and treatment of irAEs, particularly as the American College of Rheumatology does not have published resources to guide rheumatologists on the management of these entities.

Table 1: Comparisons amongst the available guidelines to guide evaluation and treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced arthritis

| Severity | Interventions | ASCO | ESMO | NCCN | SITC | Summary |

| Grade 1 (mild) Mild pain or stiffness One to two joints | ICI | Continue | Continue | Continue | Continue | Continue ICI |

| Anti-inflammatory | Consider NSAIDs | Consider NSAIDs | NSAIDs Consider prednisone 10–20 mg/day |

| Consider NSAIDs | |

| Other | Analgesics | Analgesics | Consider referral |

| Analgesics | |

| Grade 2 (moderate) Moderate pain, stiffness, limiting iADLs One or more joints with severe inflammation | ICI | Consider holding | Continue (individualized) | Consider holding, hold if no response in |

| Continue/consider holding ICI |

| Anti-inflammatory | Prednisone Consider DMARD if not tapered to | Prednisone Consider DMARD† | Prednisone Consider csDMARD* | Prednisone Consider DMARD† if requiring | Prednisone Consider DMARD | |

| Other | Referral injections | Referral injections | Referral | Referral | Referral injections | |

| Grade 3 (severe) Severe pain or stiffness Limiting (self-care) ADLs and grade 4 | ICI | Hold (resume if grade ≤1) | Hold | Hold |

| Hold ICI |

| Anti-inflammatory | Prednisone If no improvement in 1–2 weeks add DMARD† | Prednisone Consider IL-6i >TNFi | Prednisone 20 mg, if no response in 2 weeks, increase to Add DMARD† If unable to taper by 2–4 weeks, consider TNFi or IL-6Ri | Prednisone *Consider DMARD† if requiring | Prednisone Consider DMARD†, including biologics (TNFi/IL-6Ri) | |

| Other | Referral | Referral | Referral | Referral | Referral |

*csDMARD: hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate and sulfasalazine.

†DMARD: hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, TNFi and IL-6Ri.

ADL = activity of daily living; ASCO = American Society of Clinical Oncology; csDMARD = synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; ESMO = European Society for Medical Oncology; iADL = instrumental activity of daily living; ICI = immune checkpoint inhibitor; IL-6i = interleukin-6 inhibitors; IL-6Ri = interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor; NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SITC = Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer; TNFi = tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors.

Figure 1: Identification and clinical approach to immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated arthritis

Figure adapted with permission from CARE ARTHRITIS LTD.

DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; ICI = immune checkpoint inhibitors;

IL-6Ri = interleukin-6 receptor inhibitors; NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TNFi = tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors.

Steroids

Intra-articular steroid injections can be used for grade 1–2 arthritis and in any arthritis grade as adjunct therapy. Oral steroids are considered first-line treatment for grade 2+ at a dose of 10–20 mg daily. Oral steroids at higher dosages (0.5–1 mg/kg) are often used for the management of higher-grade arthritis. A referral to rheumatology is recommended to guide steroid tapering. In our clinical experience, patients often require higher steroid doses than needed to treat traditional rheumatoid arthritis. It has been shown that there is an association between the use of high-dose corticosteroids in the treatment of irAEs and impaired survival in patients with melanoma on ICI therapy.24 This association may be due to severe irAEs (grade 3+) that often require discontinuation of the ICI as outlined in various guidelines.5,20–22 Another contributing factor may be that a second immunosuppressive agent was typically required to fully control ICI-IA at higher grades and that patients who received both steroids and second-line immunosuppression had worse rates of progression-free survival.24 Given different patterns of ICI-IA, the length of therapy will vary. Patients with RA-like presentations may be more likely to have persistent arthritis. At patients’ final visit, 18% had persistent arthritis, 26% had intermittent flares and 54% had a self-limited pattern.25 Frequent rheumatology visits, every 4–6 weeks, are recommended to assess response to treatment, and tailored treatment plans are advised based on the variability in length of time treatment required and dose of steroids needed.21

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

There are no prospective published data and very little retrospective data available to guide the use of different DMARDs in the treatment of ICI-IA. The effects of the use of DMARDs on tumour outcome and ICI efficacy are also poorly understood. Prior studies suggested that enhanced immunosuppression, such as with higher doses of steroids, can be associated with worse outcomes. However, this was confounded in retrospective studies as seen in patients with more advanced malignancy with brain metastasis who were receiving steroids for this indication.26,27 Guideline recommendations typically suggest conventional synthetic DMARDs as an initial therapy (such as methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine or hydroxychloroquine).5,20–22 If additional agents are required, TNFi and IL-6i are recommended.26

Biologics

There have been some reports that the use of TNFi is associated with worse cancer outcomes.28–30 However, there are also data suggesting no worsening prognosis or tumour progression with the TNFi for ICI-induced irAEs.31,32 One prospective study found that combining an ICI with a TNFi had a favourable tumour outcome.33 Several studies have shown that the use of an IL-6Ri can enhance the tumour-specific Th1 response and thus anti-tumour effects in conjunction with the administration of an ICI.34,35 The efficacy of IL-6Ri in the treatment of irAEs has been studied; however, there is a lack of large prospective data to support their use.36,37 As data regarding the use of different biologics are conflicting regarding the treatment of irAEs, care must be taken in choosing an appropriate agent in each individual case until more prospective data become available.

Continuation of immune checkpoint

inhibitor therapy

Several different systems are used to grade irAEs, including guidelines from the ESMO, ASCO, NCCN and SITC.5,20–22 Treatment is determined by the grade of irAE that is experienced by the patient. Grade 1 (mild) toxicity often involves conservative management with NSAIDs, analgesics and continuation of ICI therapy. Grade 2 (moderate) toxicity may require holding the ICI as well as steroid injections in particularly troublesome joints, oral prednisone (usually 10–20 mg/day), NSAIDs, DMARDs and referral to a rheumatologist. Grade 3 (severe) toxicity typically requires holding the ICI, higher doses of oral steroids, DMARDs (possibly biologic DMARDs) and referral to a rheumatologist. It is recommended not to restart ICI therapy before symptoms improve to a grade 1 level or fully resolve. It is imperative to use shared decision-making with the patient and oncology colleagues, as immunosuppression can theoretically decrease the effectiveness of ICI therapy and put patients at additional risk for opportunistic infections.

Conclusion

ICIs have revolutionized cancer treatment and have had a significant impact on patients’ outcomes; however, there have been increasing reports of different irAEs associated with their administration. Evaluation of the degree of irAE is straightforward with the use of several different grading systems, which assist in the determination of treatment options. The therapeutic methods used in treating ICI-IA are tailored to each patient and their individual symptoms. These may include DMARDs, steroids and biological agents such as TNFi and IL-6Ri. Shared decision-making with patients and their oncologists is necessary for developing a treatment plan, particularly as evidence regarding the use of immunosuppressive medications may have potentially a negative impact on cancer outcomes.